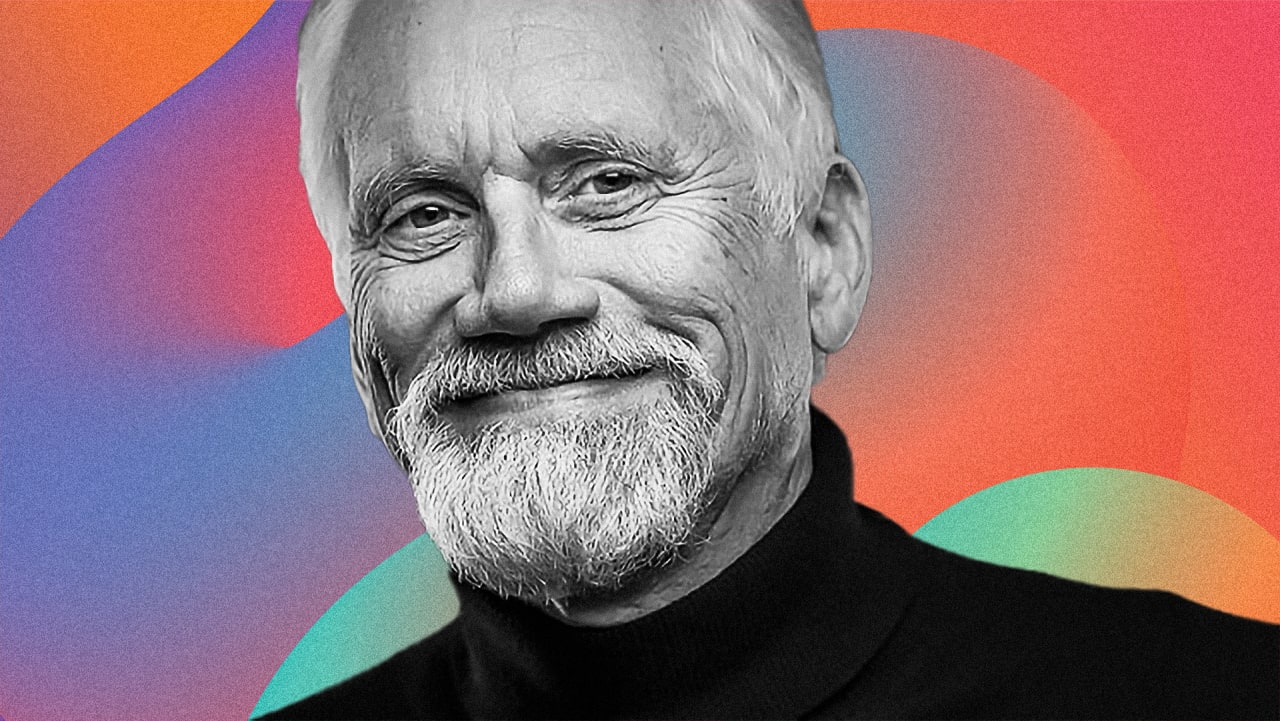

The advertising industry lost one of its icons with the September 30 passing of Wieden+Kennedy cofounder Dan Wieden at the age of 77.

As I wrote last October, when Wieden’s agency cofounder David Kennedy died at the age of 82, if there was a Mount Rushmore of American advertising, doubtless both Wieden and Kennedy would be there. Sure, Wieden famously came up with “Just Do It,” but the Portland, Oregon, agency they started has since spent the past four decades creating iconic ads and campaigns for Nike, Honda, McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, ESPN, and many other major brands. As a result, W+K has become the world’s largest independent advertising network with offices around the world and more than 1,500 employees.

What makes the agency’s story even more compelling is that scale was never really the goal, but rather an outcome of a separate aim. Wieden’s intention wasn’t to build a huge advertising agency, but rather a place where creative people from all backgrounds could, in his words, do the best work of their lives.

A big part of the Wieden+Kennedy origin story is that because they refused to leave Portland, the agency couldn’t compete for ad talent against major agencies in places like New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. So they didn’t look for ad talent specifically. They just wanted creative people who could apply their ideas to brand problems. Wieden’s belief was that the agency wasn’t successful despite its location and non-traditional talent pool, but because of it.

The advertising industry is practically unrecognizable from the one in which Wieden launched his career and built his company. Our fragmented media landscape no longer provides brands and advertisers with a small handful of options in order to break through to pop culture. Instead, it’s a 24-7 firehose of content from all directions, endlessly demanding our attention.

Now, creatives like Hallie Tut and Estée Lalonde use such tools as YouTube, SoundCloud, TikTok, and more as the new launchpads of creative brand work. Then there’s the pull of tech platforms, attracting creative minds that in previous generations may have migrated to adland. Even within the industry, agencies now compete for the best and brightest with—and within—giant public holding companies, global consultancies, as well as the brands and tech platforms themselves.

So as the industry continues to mourn the passing of one of its modern legends, where does the next Dan Wieden come from, and what is the path they might take?

Vann Graves is executive director at VCU Brandcenter, a portfolio school that Wieden once served as a founding director. Graves readily admits that the advertising industry doesn’t create icons like it used to. “It’s not that we don’t need them, but I think there isn’t any time,” says Graves. “You don’t know who made that Super Bowl spot anymore, because how we make work has changed, the business has changed, and how we do it has changed.”

For Michael Leibowitz, founder of the award-winning independent agency Big Spaceship, he recognized a challenge facing advertising upon a recent visit to the Virgil Abloh exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. “If he had come up in advertising instead of architecture, I don’t know that he would’ve had the massive cultural impact he did,” says Leibowitz, who founded his agency almost 23 years ago. “When I ask myself why that is, I think it’s that for whatever reason, [the ad industry’s] silos seem incredibly rigid. What I love about Dan was that he fostered an organization that maintained an equilibrium between welcoming misfits and odd ones—and a standard of excellence. That’s all too rare.”

The ad industry has long struggled with attracting and supporting a diverse pool of talent and, as importantly, building paths for that talent to become industry leaders. One need look no further than Walter Geer’s “Black Madison Avenue” discussion from last March to see that there is still much more progress to be made.

Of course, there are a laundry list of programs, internships, and initiatives throughout the ad industry with that very goal: to uncover, nurture and build talent. Formal ad portfolio schools like VCU Brandcenter are but one notable avenue. Others include programs like the One School, which offers affordable access and education to aspiring Black creatives, and Ryan Reynolds’ Creative Ladder, founded this past summer as a 501(c)(3) organization for students and emerging talent from marginalized communities interested in marketing, advertising, design, and commercial production.

Wieden himself worked his entire career trying to build a pipeline to answer this very question. In fact, he oriented his entire company around that goal. Caldera, the arts organization he founded in 1996, started as a summer camp and has evolved into a pipeline of creative talent and opportunity in and of itself.

The next Wieden may not come from within the walls of W+K, but the agency has certainly tried to maintain a structure that could make it possible. In 2004, it set an industry precedent with a six-month, paid creative accelerator program (dubbed The Kennedys since 2011) that searched for talent from a diverse, non-traditional range of backgrounds, teaching students the foundation of its business and assigning them real client projects. W+K brand executive Charity Pourhabib started ADMagic in 2021 to give HBCU students access and exposure to ad industry careers. Last summer, W+K launched a partnership with The Roc Nation School of Music, Sports & Entertainment at Long Island University, with a course on how culture gets made, and this year it launched a new, paid residency program in New York called Rotate, to give participants experience at multiple creative companies.

Even beyond formal programs, the agency is just always on the lookout. Back in 2020, after reading about NBA podcasters and @NBABubbleLife twitter in The Los Angeles Times, the agency offered Tray Edwards and Drew Ruiz jobs in the New York office. Edwards is now part of the agency’s social creative studio Bodega, and Ruiz is a creative, whose most recent work includes the new McDonald’s Cactus Plant Flea Market collaboration.

W+K CEO Neal Arthur says that despite the increased competition, they’re finding that people still really want to be a part of a creative culture and community. “They also see the opportunities we can provide at scale,” says Arthur. “Obviously someone like MrBeast has no need to get into an advertising agency, but for many people, the opportunity to work with brands like Nike, McDonald’s, and [AB InBev] at this scale is still super appealing.”

Another major component to Wieden’s impact was his commitment and belief in independence. In fact, in 2015, all the company’s shares went into a trust to ensure it would always remain so. Wieden told an industry gathering at the time, “We will die before we sell.” This is a potentially thorny statement in an industry dominated by global, public conglomerates, but the path to continue Wieden’s legacy does not lead through their doors. Any future ad legend will bubble up from or start an independent agency, and there certainly are plenty trying. Arthur says it’s difficult, if not impossible, to maintain creative ideals when you’re part of a larger public company. “You’re beholden to shareholders and analysts, so suddenly you’re following trends of where the business is going, as opposed to being true to your vision,” he says.

Leibowitz agrees. He says there’s still plenty of room out there to experiment if you have the stability, security, and capital to do so—as well as enough independence to want to do it. “What does the world actually need, and where can we meet that? I think the world needs less advertising, and more creativity,” he says. “Dan understood that. The work they’re making, and how they’re finding talent in the spaces they wanted to play in, like the social studio (Bodega), that’s smart. That’s not just creative, it’s good business.”

To think about where and when the next generational advertising talent and entrepreneur may emerge, Paul Venables says it’s important to remember Wieden’s own path. Venables founded his own independent agency, Venables, Bell & Partners, in 2001. “He didn’t come from an exciting trend, a hot category, a new technology, or even an interesting part of the country,” says Venables, referring to Wieden’s start writing ad copy for a lumber company. “Where Dan came from was rather ordinary. The path isn’t meaningful; the mindset is. The next Dan Wieden will come from a place of fearless creativity, with just enough confidence to believe they can and will do it better.”

Arthur agrees that this isn’t about a specific path. “I have no idea how brands will connect with culture in 10 years, but I do know that creativity and creative culture will be at the core of it,” says Arthur. “That was always the heart of Dan’s thing, and it’s still true.”

* This article was originally published here

Comments

Post a Comment