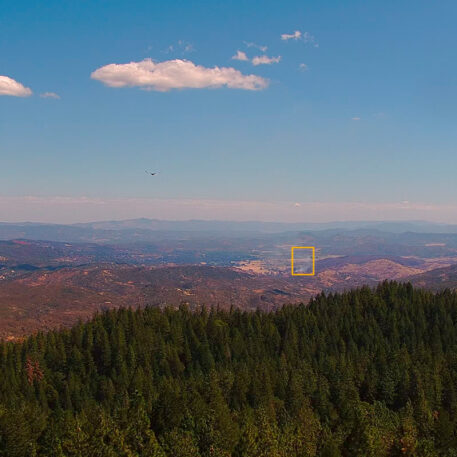

When a fire started in a forest near Big Sky, Montana, on a September afternoon last year, a camera perched on a mountaintop detected the first plume of smoke. The camera, from a startup called Pano, had been installed only a week earlier as part of a pilot; the local fire department planned to test it when they did controlled burns in the area. But when a wildfire unexpectedly started, the tech happened to already be in place.

[Image: Pano]

[Image: Pano]

A bystander also spotted the fire, and called 911. But the technology—which uses artificial intelligence to spot potential fires, and then sends the data to a team who can confirm it and alert firefighters—helped quickly lead a fire crew to the precise spot it was burning, which can be difficult to locate, especially in remote areas.

[Image: Pano]

[Image: Pano]

“Pano uses our algorithm to determine the exact latitude and longitude of the fire so that first responders can head directly there,” says Sonia Kastner, founder and CEO of Pano. When bystanders call 911, a majority of the calls end up being false alarms; Pano’s technology sends firefighters a text with video of the fire, so they can virtually confirm that it’s real. The data is also designed to be easily shared with multiple fire agencies for a strategy called “rapid initial attack,” in which agencies coordinate to fight a fire when it’s still small enough to control, rather than waiting for it to grow.

The startup is part of a surge of new work aimed at avoiding the type of extreme, record-breaking fires that keep increasing in Western states, fueled in part by drought and heat linked to climate change. A new $35 million venture capital fund called Convective Capital—focused only on what it calls “firetech,” including Pano—launched today. Separately, a new nonprofit called Megafire Action also recently launched, focused on how to end megafires, high-intensity fires that quickly spread over 100,000 acres or more. And the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law include billions to help better manage forests, including “prescribed” burns that can clear away dead trees and branches, which have built up after decades of fire suppression.

Fire is a natural part of the landscape, but what’s happening now looks very different than it did in the past. In California, the area that burns each summer has grown by around 800% over the past five decades. The state’s 10 largest wildfires since modern record keeping began have all happened in the past decade; in 2020 alone, 4.3 million acres burned, an area five times larger than Rhode Island. As trees burned that year, they released as much CO2 as 24 million cars.

Part of the problem is climate change, as extreme heat, drought, and tree-killing diseases make it easier for forests to burn. But the way forests have been managed also plays a critical role, and technology can help. Megafires are not inevitable, argues Matt Weiner, cofounder and CEO of Megafire Action. “This is a solvable problem,” he says. “And therefore, policymakers need to act with greater urgency to solve it.”

***

A helicopter flies with a load of water to the Bootleg Fire, July 15, 2021. [Photo: Payton Bruni/AFP/Getty Images]

A helicopter flies with a load of water to the Bootleg Fire, July 15, 2021. [Photo: Payton Bruni/AFP/Getty Images]

In Southern Oregon in 2021, when the massive Bootleg Fire reached a 30,000-acre nature preserve managed by the Nature Conservancy, flames were shooting 200 feet in the air. But when the fire got to an area that had been carefully managed, it suddenly changed. The flames dropped down and moved more slowly. For years, researchers in the area had been testing different “treatments” for the forest, thinning out trees in some areas and conducting prescribed burns. When the fire came through, it demonstrated what worked: In photos taken a few months after the fire, trees were still alive in the area that had been both thinned and treated with controlled burns. Across a road, in an untreated area, nearly everything had burned. (When a fire is so extreme, it can also sterilize the soil in some cases, making it hard for any new trees to grow back.)

[Image: Brady Holden/The Nature Conservancy]

[Image: Brady Holden/The Nature Conservancy]

“It’s becoming clear, as we dig into these recent wildfires, that the combination of thinning followed up with prescribed fire really appears to be the most effective way to modulate future wildfire behavior in a good way,” says Dan Porter, a forest program director at The Nature Conservancy.

[Image: Brady Holden/The Nature Conservancy]

[Image: Brady Holden/The Nature Conservancy]

For centuries, Native Americans intentionally lit small fires to help manage the landscape and prevent more destructive wildfires. But the U.S. government banned the practice in 1850, only beginning to allow it again more than a century later . And in the 1930s, the Forest Service adopted a practice of putting out every fire that started naturally. (The agency’s “10 a.m.” policy said that every fire should be extinguished by 10 a.m. the morning after it was first reported.) That meant that forests became densely packed with trees and with dead branches and leaves on the forest floor. Fires that in the past might have been small now had much more fuel, and could spread more easily.

[Image: Mitch Maxson/The Nature Conservancy]

[Image: Mitch Maxson/The Nature Conservancy]

“Fire is a natural part of ecosystems in the West, and it’s absolutely necessary,” says Megafire Action’s Weiner. “One of the reasons that we’ve seen these megafires that burn with greater intensity, and burn more acreage, is because we took good fire out of the forest for 100 years. So a big part of the overall goal here is to bring that back at scale.”

[Image: The Nature Conservancy]

[Image: The Nature Conservancy]

Prescribed burns aren’t risk-free and led to a disastrous fire in New Mexico this year. But 99.84% go according to plan, according to the Forest Service, and they’re a critical tool in preventing megafires.

New federal funding for this type of work will help, Weiner says, but it isn’t even close to enough. “It’s a tenfold increase over the annual average of what we spend on this,” he says. “But it’s still only 10% of what experts say we need to fully implement the USDA strategy of treating 50 million high-risk fireshed acres in the next decade.”

***

New technology can also help. Tech entrepreneur Bill Clerico launched Convective Capital, the new fire-focused VC fund, after seeing the need for more support for the field. New, inexpensive satellite tech, for example, has received more attention for other uses. “There’s a lot of entrepreneurs applying those technologies to fintech and stuff like that, but not so many entrepreneurs applying them to wildfire,” he says. Overstory, one startup in the fund’s portfolio, uses AI to analyze satellite images of vegetation, looking for risks like trees that could fall on power lines.

[Image: Dryad]

[Image: Dryad]

Other startups, like Pano, are focused on how to help firefighters respond more quickly to fires when they begin, and track them as they grow. A company called Dryad makes small solar-powered sensors that can attach to trees and “smell” gasses like carbon monoxide when a fire begins to smolder, far earlier than other methods can detect a fire. Others are working on more experimental technology, like Rain, a company developing drones that could automatically respond to fight fires before a fire department arrives.

[Image: Dryad]

[Image: Dryad]

Eventually, Weiner says, technology should also be able to help determine when it’s safe to let some fires burn naturally. “The dream is to be able to make very quick decisions as a fire is starting about whether that fire could burn, or whether it’s going to turn into a megafire that’ll destroy an ecosystem or cause a climate problem or impact a community,” he says.

Some companies are looking for new ways to use small trees, twigs, and branches in forests to reduce fuel. In California, Pacific Biochar collects this type of wood—which the forestry industry normally wouldn’t use—and then heats it to create biochar, a charcoal-like substance that can be added to fields to help make soil healthier. (Microsoft recently bought carbon credits from the company). Others are using “low-value” wood from forests to make cross-laminated timber.

Utility companies are racing to adopt new technology, since power lines have sparked several major fires. San Diego Gas & Electric, for example, is beginning to use new power lines in some areas that automatically switch off before they hit the ground if they detect that they’re falling. (Other power lines have been buried, or “hardened” by switching from wood to steel.) The utility is also using sensors and satellite tech both to spot fires and track weather conditions.

When a recent tropical storm brought hurricane-force winds to Southern California and there was a risk that power lines could be knocked down, the utility used software to track how much moisture was in the ground. It was able to avoid shutting off power for residents, something that’s becoming more common when fire risk is highest. “We use all of this technology to really help us understand the overall fire environment, and then that can help us use that public safety power shutoff as a tool of last resort,” says Brian D’Agostino, vice president of wildfire and climate science at San Diego Gas & Electric.

As climate change progresses, it will keep getting harder to avoid extreme fires. But there’s a significant amount that can be done, Weiner says, and it’s urgent to address immediately as part of the fight against climate change. “If we don’t do anything here, the climate problem everywhere will get exponentially worse,” he says. He points to a study that found that California’s 2020 fires essentially erased the gains that the state had made in reducing industrial emissions since 2003. “If the West continues burning as it has, it’s a really scary thing,” he says. “You’re talking about potentially getting rid of some of the best carbon sinks that we have on the planet.”

* This article was originally published here

Comments

Post a Comment